In the spiritual life of a Catholic, the Eucharist holds a central place as the most sacred and significant sacrament, an act of intimate communion with our Lord. Some receive it on the tongue and others in the hand, but does that matter? How did each of these methods arise and why? Which is the most appropriate? And which one did Jesus Christ use? What does the Church dictate? In a matter too important to shrug off, we will provide all the answers here, thoroughly documented, so that you can make an informed choice.

Notice: This article is a (human) English translation from our original Spanish site. Expect links marked in yellow, if any, to open articles in Spanish at the moment. If you are a native English speaker and want to help with Catholic apologetics, contact us, we need volunteers to spot mistranslations that must definitely be corrected.

By way of introduction, let’s start with the basics, as sadly there are many Catholics today who are not very clear on what it means to receive Communion.

What is the Eucharist

Before discussing the ways of receiving Communion, it is necessary for all of us to have a clear understanding of what we are talking about. This is not simply a symbol, contrary to what many Catholics believe today.

In His first coming, Jesus became incarnate, that is, His divinity became flesh, so that whoever saw Jesus was seeing, with their physical senses, a man of flesh (with bones, and mind and soul…), but that flesh, oh inconceivable wonder, was God Himself. The same happens with the Eucharistic bread; with our physical senses we see bread, but that bread, oh inconceivable wonder, is God Himself.

After His Ascension, Jesus promised that He would remain with us forever. But the incarnate God was not referring to a mere spiritual presence; that would not bring anything new to an omnipresent God who is everywhere. Jesus meant that although He, in the flesh, seemed to physically leave us, it was not so, for He would continue to be with us physically, albeit in a different manner—not through flesh, but through bread and wine (John 6). When He was in His physical body, His physical presence was limited to the here and now, but by changing to different physical “species,” by acquiring a new Eucharistic body, He became materially accessible to all Christians worldwide and throughout all ages. In that sense, the Eucharist is a more advanced step than the Incarnation.

If the physical body of Jesus was truly God (though truly human in its accidents), it should surprise no one that now the Eucharistic bread is truly God (though truly bread in its accidents).

Christians who accept that the Son of God became man yet find it absurd that the same Son of God becomes bread, cannot attribute their lack of faith to a logical, rational, or scientific problem. If one thing was possible, so is the other. And if Jesus showed His divinity by performing miracles, Eucharistic miracles (watch video activating English subtitles) are also countless, having greatly multiplied from the 20th century and even more in the 21st century.

Saint Paul makes it clear that receiving Communion is not merely symbolic, but truly the body and blood of Jesus. Therefore, to partake while in a state of sin and/or without understanding what one is receiving has serious consequences for the soul:

[

Therefore whoever eats this bread or drinks this cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be guilty of the body and blood of the Lord. But let a man examine himself, and so let him eat of the bread and drink of the cup. For he who eats and drinks in an unworthy manner eats and drinks judgment to himself, not discerning the Lord’s body. For this reason many are weak and sick among you, and many sleep [=are dead]. (1 Corinthians 11: 27-30)

Let us mention in passing that the Church decided to stop offering wine in Communion for several reasons, mainly for two:

- People tended to believe that the bread was the body of Christ and the wine was His blood, and that heresy was very difficult to eradicate. By removing the wine, it became clearer that Jesus was fully present in both species, not divided into body without blood and blood without body, as if we had two incomplete “Jesuses.”

- Logistical problem: If dozens of people drink from the same cup, diseases and plagues could be transmitted. Additionally, it was easy for drops to spill while drinking, which would result in profaning Christ.

Therefore, the consecrated host is truly the body and blood of Christ, His soul and divinity. By receiving the host, we are “eating and drinking” the body and blood of Christ. The same incarnate Jesus who walked the earth is the one we consume in Communion, although under a different species. The host is the whole Jesus.

Let us now briefly discuss what happens in the Eucharist, that is, what the Mass essentially is.

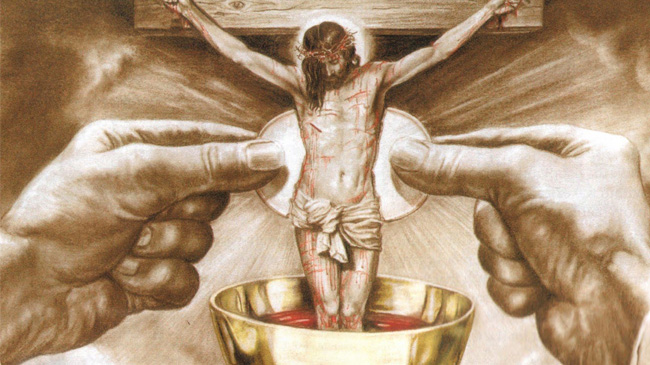

The Mass is a meal and is community, yes, but above all, it is the “re-presentation” of the sacrifice of Calvary. In the Old Testament, God commanded us to perform animal sacrifices as worship and expiation for our sins. This duty did not expire with Christ but reached its culmination in a unique and definitive sacrifice in which the Paschal lamb was replaced by the “Lamb of God” Himself, that is, Christ, who by shedding His blood on the altar of the cross performed the sacrifice that put an end to all sacrifices. At the same time, He gave us the means to spiritually unite ourselves with that sacrifice which occurred in Jerusalem around the year 33. In the spiritual realm, there is no time or space, making it spiritually possible (for it is God’s will) that we, in the 21st century, can, at each Mass, transport ourselves to that moment and place where Jesus expired on the cross of Calvary.

We do not sacrifice Jesus at each Mass; rather, at each Mass, we return to the foot of the cross at Calvary and unite ourselves with that one sacrifice Jesus offered with His death. There, we also spiritually unite with all Christians of the present, past, and future who have celebrated and will celebrate the Eucharist, and even with the angels, as well as, of course, Mary and John. It is also our opportunity to unite our own sacrifices with the sacrifice of Christ (Colossians 1:24) and to place our sorrows and petitions on the altar—an enormous opportunity that is a pure gift from God and one that many do not know how to take advantage of.

The sacrifices of the Old Testament were the means God established for worshiping Him, but they had a very limited effect in terms of grace, only forgiving certain sins. However, the sacrifice of Jesus, being infinite, had an infinite effect, opening the gates of heaven for us and offering us the possibility of being reunited with God. To understand the functioning of Jesus’ sacrifice, we need to understand the functioning of the Old Testament sacrifices, as they were established by God through Moses to be a figure (typos, premonition) of what Jesus’ sacrifice would be. This is what Christians re-enact in the Mass.

And these are the elements of the Mosaic sacrifice that we see fulfilled (and sublimated) in the sacrifice of Jesus:

- 1- Only priests can make sacrifices. Protestants do not perform sacrifices, which is why they do not have priests but pastors who guide their congregation. Jesus is the High Priest who offers His own sacrifice (Hebrews 9:11-12), and Catholic priests re-enact Jesus’ sacrifice by performing it in persona Christi, that is, allowing Jesus to act through their bodies. Strictly speaking, in the Mass, it is not the priest who offers the sacrifice, but Jesus, through the priest, who does so.

- 2- An altar is needed, a raised surface where the sacrifice will be made. Jesus used the raised cross, and priests use elevated altars (either block type or table type) but with a cross upon it.

- 3- A valuable victim is needed. In the Mosaic law, this is an unblemished lamb, and in the New Testament, it is the most valuable victim imaginable—God Himself made man, without blemish. In the Mass, He materializes in the host, becoming one with it.

- 4- Once the sacrifice is offered, it must be eaten so that the sacrifice not only pleases God but also bestows His graces upon the offerers. The Israelites ate the sacrificed lamb. This is why we receive Communion; that is, we eat the flesh of the sacrifice so that God may bestow His graces upon us. This explains why Jesus announced the grace that derives from His sacrifice—eternal life. But for that grace to take effect in us, He tells us it is necessary to eat the sacrifice, that is, Himself! Otherwise, we will not benefit from His death and will not have eternal life:

[

I am the living bread which came down from heaven. If anyone eats of this bread, he will live forever; and the bread that I shall give is My flesh, which I shall give for the life of the world. (John 6:51)

And then He reinforces this idea: it is not enough for Him to die to save us; we must eat His flesh for that salvation to reach us:

[

Then Jesus said to them, “Most assuredly, I say to you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink His blood, you have no life in you. Whoever eats My flesh and drinks My blood has eternal life, and I will raise him up at the last day. For My flesh is true food indeed, and My blood is true drink indeed. (John 6: 53-55)

Therefore, those who believe that the Eucharist is merely a symbol, a remembrance without any effect, cannot benefit from either the Mass or Jesus’ sacrifice on the cross. If you do not receive Communion (at least once a year), and if you do not receive it in a state of grace and knowing that what you are eating is the body of Christ (as Saint Paul reminded us), you will not have eternal life. This is something that both Protestants and would-be Catholics who have lost their faith in the Eucharist should reflect upon. In case of doubts, read the entire chapter of John 6 and you will see how Jesus insists that He is not speaking symbolically, but very literally when He speaks of eating His flesh. To the point that some of His followers leave because they believe His words are outrageous, and instead of stopping them and explaining Himself better, He turns to His apostles and asks if they also want to leave. The apostles were probably as confused and scandalized by these words as the others, but Peter reaffirmed their faith by accepting the truth of those words, saying, “Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life, and we believe and know that you are the Holy One of God.” (John :68-69) In other words, we do not understand, but you are God, and that is why we believe it.

On the Tongue or in the Hand

This is a very controversial topic today, requiring us to navigate through a jungle of misinformation and misunderstandings. However, it is not without importance. To be well-informed, let’s look at how Christians have carried out this act of receiving the body of Christ throughout history over these past 2000 years and why.

At the Last Supper

It is considered that during this Passover meal, Jesus instituted the Eucharist. But didn’t we say that the Eucharist is Calvary? Both things, yes. We have said that the sacrifice of the Mass is not a new sacrifice but rather uniting spiritually with the sacrifice of Calvary, because in the spiritual realm there is no space, and there is also no time (something confirmed by Einstein in his Theory of Relativity, for the more skeptical). This means that it is not only spiritually possible for a 21st-century Christian to be present with Jesus at Calvary, but it is also equally possible for a person before Calvary to spiritually unite with future Calvary. Without time, the past, present, and future are the same point. That is what Jesus did at the Last Supper; He acted as the priest (at the Supper) and offered the sacrifice of His own body (at Calvary), bringing the entire assembly present (the apostles) to the future moment of His crucifixion. That is why the Eucharist is a Supper, but a Supper in which the diners are transported to Calvary.

[

For this is My blood of the new covenant, which is shed for many for the forgiveness of sins. (Matthew 26:28)

“Which is shed” is expressed in the original Greek as ἐκχυννόμενον (shed), a present passive participle. In the Koine Greek dialect, used in the New Testament, the present participle can have a present sense (is being poured out) or a near future sense (will be poured out), similar to the English present participle (I’m playing tennis… now/tomorrow). Therefore, the translation used by many Bibles, which says “which will be shed for many,” is more accurate. This is because the cup of blood that Jesus offers to His apostles is the blood of the future sacrifice that will occur the next day (He is not pouring out His blood at that moment), just as today’s Eucharist is the blood of the past sacrifice that occurred 2000 years ago.

At that supper, Jesus consecrated the bread and wine and gave Communion to His apostles. This is the first time the Eucharist was received, and it is Jesus Himself who officiates the Mass. Therefore, it would be interesting to know how Jesus gave Communion to the apostles: on the tongue or in the hand?

People simply assume that He distributed the bread in the hand, as they see in movies, but there is nothing in the Bible that leads us to that conclusion. Most also assume that He broke and distributed bread like what we eat today, with leaven, but it was not so; it was unleavened bread, without leaven, that is, more like Mexican corn tortillas—but rigid—than today’s leavened bread. Over time, it was administered in the form of thin, small wafers to minimize the risk of crumbs falling, since Jesus is also fully present in the crumbs.

Although the Bible does not specify the manner of receiving Communion, we can draw on historical knowledge to make an assumption. Even in biblical lands until recently, it was customary for the host (in this case, Jesus) to honor the guests by giving them a special morsel from his plate, placing it in their mouths with his own hands, which was considered an act of intimacy.

Note: You can find confirmation of this biblical custom in books such as "Manners and Customs of the Bible" by James Freeman, "The New Manners and Customs of Bible Times" by Ralph Gower, or "Jesus and the Last Supper" by Brant Pitre.

If Jesus followed this same custom, with the Eucharistic bread being the most special delicacy imaginable, He would have broken a piece and given it directly to the apostles in their mouths, instead of passing the bread for them to break or giving them pieces in their hands, which would be less intimate. In that culture, the act of giving them the bread in their mouths would be considered a great honor, while giving them the bread in their hands would be an act that would not carry any special honor for either the bread or the guest.

Although we have said that the Bible does not specify how Jesus distributed the bread, knowing this ancient custom, we can find a hint of how Jesus gave Communion. This would be at the moment when He announces that He will be betrayed, and responding to John, He says:

[

“It is he to whom I shall give a piece of bread when I have dipped it.” And having dipped the bread, He gave it to Judas Iscariot, the son of Simon. (John 13:26)

It is significant that it is precisely John who tells us this, as he is the only one who does not mention the blessing of the bread and wine during the Last Supper (although, of course, he takes for granted that it had to be performed as it was part of the Passover meal ritual, and he develops the Eucharistic theme in his aforementioned chapter 6). In this account by John, the only reference to the distribution of the bread and wine is this one, where Jesus dips the bread in the wine and gives it to Judas.

When Jesus said that the traitor was the one to whom He would give the morsel dipped in wine, if He had only given it to Judas, it would have been clear that Judas was the traitor. However, the apostles did not understand who the traitor was. This only makes sense if Jesus had given the bread dipped in wine to all of them, so Jesus’ words did not serve to single out the traitor but only to indicate that the traitor was one of the twelve, just as a little earlier when Jesus mentioned a biblical quote saying, “He who eats my bread has lifted his heel against me” (John 13:18 cf Psalm 41:9) (but they all ate His bread!).

Now then, if this hint from John is correct, we must understand that Jesus gave Communion to His disciples by giving them a piece of bread dipped in wine. We have already mentioned that there is evidence of this custom to honor the guest (and the special food) by giving them the morsel in their mouth, but we also have logic to aid us: if you want to dip bread in wine and distribute it to people, would you give it to them in their hands to get them messy? Of course not. Imagine you have a very special guest at your home and you want them to try your mother’s delicious bun with a cup of hot chocolate. You cut a piece of the bun, dip it in the warm chocolate, and… would you give it to them in their hand? Obviously not. You might say that you would give the piece of bun in the hand for them to dip it in the chocolate, but we know that is not what Jesus did; Jesus dipped the bread and then gave it.

So those who claim that Jesus gave Communion to the apostles in the hand do so without any foundation. Rather, the indications clearly point to the contrary—that Jesus gave Communion in the mouth. But in any case, this is only the beginning. Let us continue through history to see what happened with Communion thereafter.

In the Early Church

In the first centuries, there are many texts that discuss the Eucharist, its significance, transubstantiation, consecration, etc. However, we do not find specific details on how the early Christians received Communion, aside from a few ambiguous references. It will be in later texts where we will gradually find clearer indications.

Since the liturgy and customs, although built on the same foundation, had variations between different regions, it is not possible to generalize. However, the oldest text describing clearly Communion in the hand is usually attributed to Saint Cyril of Jerusalem:

[

"When thou dost approach, come not with thy palms extended nor with thy fingers spread, but make thy left hand a throne for the right, which is to receive the King. In the palm of thy hand, receive the Body of Christ, saying: 'Amen.' Then, sanctify thine eyes with the touch of the holy Body." (Mystagogic Catechesis 5, 21 ff., circa A.D. 350)

But even in that very citation, we see the emphasis always placed on ensuring that no particle is lost. The previous citation continues as follows:

[

"And, after partaking, take heed that thou lose no part of Him, for if thou lettest fall aught, it is as though thou hadst lost one of thine own members. Tell me: if anyone had given thee grains of gold, wouldst thou not keep them with all care and be on guard lest thou lose any of it or let any fall? How much more carefully, then, shouldst thou keep watch that no particle fall from thee of what is more precious than gold and precious stones?" (Cyril of Jerusalem, Mystagogic Catechesis 5, 21 ff., circa A.D. 350)

The Church, both today and always, has made it clear that the body of Christ is not broken in the Eucharist, but is always whole and complete in each of the species and in each of the fragments, no matter their size. Thus, even the particles (visible or invisible) contain the entire body of Christ.

Note: Normally, for simplicity, we refer to "the Body of Christ," but it is understood that the Eucharist is not just the body; it is the body, blood, soul, and divinity of Jesus.

The next text we find discussing Communion in the hand is from just 22 years later and presents us with a very different perspective:

[

"It needeth not be pointed out that, in times of persecution, it is no grave offense when one is compelled to take Communion with one's own hands in the absence of a priest or minister." (Saint Basil the Great, Letter 93 (or 89), circa A.D. 372)

This can also be read as indicating that it is indeed a grave offense to take Communion with the hand if there is no persecution or if there is, but a priest is present to administer it. Or at least that was the belief in Cappadocia, because as we have seen, according to Saint Cyril, during the same period, Communion in the hand appeared to be the norm in Jerusalem. It is true that in the previous quote it could be interpreted that the real offense is not so much receiving Communion in the hand but grasping the Eucharist with the hand, but the previous quote continues in this manner:

[

"In Alexandria and Egypt, all the laity receive and hold the Holy Mysteries in their own hands and communicate themselves" (or 'bring it to their lips with their own hands,' according to other versions).

Here it is clearly stated that the faithful “receive” (not “grab”) Communion “in their own hands.” But the fact that this is mentioned as a peculiarity of Egypt means that it was not the common practice throughout the Church, but a difference. Thus, it seems that both forms of receiving Communion coexisted in the early centuries (at least between the 4th and 8th centuries).

References to the manner of receiving Communion increase by the 7th century, and all seem to indicate that Communion in the hand existed (we do not know if it was widespread or minor), but it was already considered a deviation that needed to be corrected:

[

"It shall not be given [to the laity] in the hand, but in the mouth." (Synod of Rouen, A.D. 650)

"Let none of the laity receive the Eucharist in the hand; all must receive it on the tongue." (Synod of Braga, A.D. 675)

"Canon 36: It is not permitted for women to receive Communion in the hand." (Council of Auxerre, A.D. 695-700)

**Note:** I have not been able to verify these quotes due to lack of access to the original records, and I have relied on the authority of several secondary sources that I consider trustworthy.

And so it was in the Western Church, but it seems that in the Eastern Church, it was quite the opposite:

[

"To those who receive Communion, the body of the Lord shall be administered in the hand with the palms of the hands in the form of a cross. However, we have not found in the authority of the apostles or in the antiquity of the church that laypeople have distributed Communion." (II Council of Trullo, A.D. 692, composed only of Eastern bishops and never recognized by the Roman Church)

In this canon, it is established that, at least from then on, Communion in the hand will be the norm for the Eastern Church, but it expressly rejects the possibility of laypeople distributing Communion, as it is considered too sacred for unconsecrated hands.

The interesting point is that we see in this canon a clear tension: if laypeople can receive the host in their hand, why should they not be able to distribute it to others (share it)? This contradiction could be resolved by allowing laypeople to distribute Communion (as often happens in practice today in the West), but this did not occur in the Eastern Churches. Shortly after this council, they opted to eliminate the dissonance through another approach, more respectful of the sacred, by not allowing laypeople to touch the host under any circumstances, not even to receive Communion themselves. This solution also addressed the serious issue of the possibility of particles of the bread falling, a longstanding concern as Saint Cyril warned us above.

This ancient concern about particles only increases, and we find more and more texts warning about the danger of losing particles, while also emphasizing the great reverence that must be shown toward the Eucharistic bread. For example, we have the testimony of Pope Leo I (5th century) and Saint Gregory the Great (6th century). This utmost reverence will gradually spread the practice of receiving Communion on the tongue for these reasons:

- 1- Only consecrated hands (those of priests) can touch the Body of Jesus.

- 2- By placing the host directly on the tongue, the much-feared loss of particles is radically avoided, preventing the body of Christ from potentially falling to the ground and being trampled.

- 3- It prevented certain individuals from taking the host for profane or satanic rituals.

- 4- It emphasizes the notion that the Eucharist is a divine grace, a gift, and therefore we are fed; it is not something we procure for ourselves with our hands as if it were ordinary food.

It is possible that this mentality, which forbade profane hands from touching the most sacred thing on earth, was greatly influenced by the case of Uzzah. When he touched the Ark of the Covenant with his hand, contravening the divine prohibition against touching it, he was struck dead. If the Ark was sacred for containing the spirit of God, the host is even more sacred as it contains not only His spirit but also His body.

It is believed that by the 8th century, the practice of receiving Communion on the tongue had become general throughout the Church, though not universal, with remnants gradually disappearing. In 1271, Saint Thomas Aquinas explains why this form is the most appropriate:

[

Summary: The Body of Christ should not be touched by anything that is not consecrated, just like the sacred vessels, and the reason is the veneration due to this sacrament. Therefore, it is customary for only the priest to touch this sacrament and distribute it with his own hands. (Read the full text in Summa Theologica, Part III, Question 82, Article 3)

But this did not only happen in the Roman Catholic Church. In all Eastern liturgical traditions we also find the practice of receiving communion on the tongue established. This demonstrates that the deepening devotion to the Eucharist and its sacredness led all different churches to converge unanimously on communion on the tongue only, as a logical and inevitable development of Christian beliefs in transubstantiation, first relegating and then prohibiting the also existing practice of receiving communion in the hand.

Eastern churches typically distribute the bread soaked in wine to the faithful using a liturgical spoon (called a “lavida“), reminiscent of how John describes Judas receiving communion (and by implication, the others as well). Some Eastern churches, like the Armenian Church, administer communion on the tongue without using a spoon. In both cases, no layperson touches the consecrated host with their hands in the Eastern tradition. Even during the Covid-19 pandemic, measures such as disinfecting the spoon after each use or encouraging believers to bring their own spoon from home were implemented, but there was never permission granted to touch the host, let alone a mandate as seen in the Roman Church.

Protestants and the Eucharist

And thus we arrive at the 16th century, when the Protestant Break occurred and its heresies spread. Since the Eucharist is the foundation of Christianity, it’s no surprise that Calvin and others sought to abolish the doctrine of Real Presence to solidify their rejection of the Catholic Church. The result was a loss of reverence towards the Eucharist, which led to the widespread practice of communion in the hand among these Protestants. Luther, on the other hand, maintained belief in a certain form of Real Presence, albeit in a significantly different manner that diminished its value. However, this “half-presence” was enough for Lutherans to continue receiving communion in the mouth until the late 19th century. By the 20th century, communion in the hand was common among all Protestants; among Anglicans, those who believed in Real Presence received communion on the tongue, while those who did not received it in the hand.

Protestants encourage communion in the hand as if it were ordinary food and not something sacred. People are to receive or take the bread with their hand and feed themselves, just as they would with common bread at home, and moreover, they do so standing. Therefore, the outward form of communion was likened to a bread distribution line for the poor, where someone with a basket would distribute bread and people would walk up in line to take their piece and eat it. This change in practice did not immediately make people stop considering the host as something sacred overnight, but it did mark the beginning of the end of that belief, especially for subsequent generations. Seeing this divine bread treated in such a secular and ordinary manner led them to perceive it as nothing more than secular and ordinary, even though it might hold a special symbolic value.

And this worked so well that later, when the Anglican Church became more Protestantized, the more radical members advocated for imposing communion standing and in the hand as an effective and peaceful tool to eradicate belief in transubstantiation in England.

Martin Bucer (16th century), advisor to the Anglican Reformation, stated that the Catholic practice of not giving communion in the hand was due to two “superstitions“: “the false honor that is claimed to be paid to this sacrament” and the “perverse belief” that the hands of ministers, by the anointing received in their ordination, are holier than the hands of the laity. Communion in the hand helped people to abandon these two Catholic beliefs: the Real Presence and the priesthood. The host became a mere symbol and therefore did not deserve special reverence, and the priest became a simple shepherd, a preacher, and a director of ceremonies, but as lay as anyone else. Thus, when Protestant practices went further (for example, throwing away leftover bread), they encountered little opposition, as no one believed anymore that this bread was really anything more than bread.

Meanwhile, Catholics continued to receive communion always kneeling and on the tongue, with utmost devotion to the Eucharist that was even reinforced after the Council of Trent. From this point onward, one form or another of receiving communion became closely associated with either Catholic or Protestant theology.

And so things continued until modernism began to undermine this and many other beliefs from within the Catholic Church, especially from the late 19th century onwards. Without denying the Real Presence, a different relationship with the sacramental Jesus was sought. The new idea that began to spread was more or less this: let us stop being subjects of Jesus and become His brothers; brothers are equals, any gesture of submission is contrary to human dignity, elevated by Jesus to His own level. This sounds very good to the ears of the modern democratic man, though at the cost of ignoring much of the Bible.

Vatican II

Contrary to what many think, the Second Vatican Council did not change the custom of receiving Communion kneeling and on the tongue. It was after the council, under the ethereal umbrella of what the modernists called (and still call) “the spirit of the Council,” that in the whirlwind of reforms that were set in motion (most of them ignoring the Council), the practice of receiving Communion standing and in the hand was attempted to be introduced, something that had been spreading for several decades in the Netherlands and surrounding areas.

We saw earlier that since the Protestant Break, the practice of receiving communion in the hand became associated with Protestant theology. That the epicenter of this Catholic disobedience was in the Netherlands is no exception to this rule. In the Netherlands, 60% of the population was Protestant, and their ideas had deeply penetrated into Catholic dioceses by the mid-20th century. When the Dutch episcopate published their “New Catechism,” it was so plagued with “doctrinal errors” (or rather, heresies) that the Holy See had to impose numerous modifications (59 in total). Among other things, it cast doubt on the real and substantial presence of Christ in the Eucharist and denied any kind of presence of Jesus Christ in the particles that were detached. There was also confusion between the common priesthood of the faithful and the hierarchical priesthood. But despite the Vatican corrections, the Dutch clergy had already assimilated Protestant theological ideas regarding the Real Presence and the priesthood, denying both. Thus, just as Protestants and Anglicans did centuries ago, the Dutch clergy disregarded communion on the tongue because it clashed with their Protestant Eucharistic theology. If the Eucharist is more of a symbol, they thought, it is more appropriate to take it in the hand.

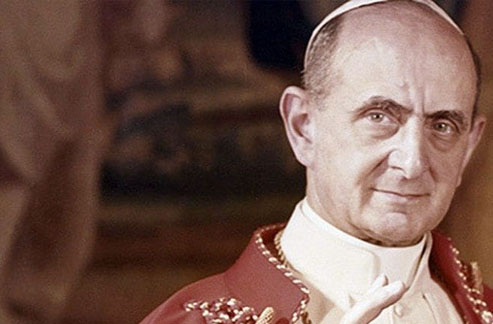

During the confusion and upheaval that occurred immediately after Vatican II, these areas intensified their pressure. Pope Paul VI made several attempts to suppress this prohibited practice, but without any success (similar to the rebellion we see today in Germany). The rebellious dioceses felt justified by the wave of changes unleashed by the Council. Finally, with numerous fronts open, the Pope decided to survey the entire episcopate to consult them on this issue: whether it was lawful to allow these dioceses to legalize what had already become an established practice in them – that is, to give official permission to the Eucharistic abuse. The vast majority rejected such a possibility, reaffirming that communion can only be received on the tongue.

Pope Paul VI felt supported in this way to settle the matter by reaffirming that the only valid way to receive communion was on the tongue. However, as seen in “La Riforma Liturgica 1948-1975” by Monsignor Annibale Bugnini, they convinced the pope that attempting to enforce the prohibition would provoke a violent reaction from the rebellious dioceses, which would undoubtedly persist in their disobedience. This would further undermine papal authority without achieving any positive outcome.

That’s why Paul VI felt compelled to disregard the opinion of the majority of bishops worldwide and yield to the disobedience of a few in an attempt to prevent a greater evil, or so he thought. Thus, in 1969, the Congregation for Divine Worship issued the instruction Memoriale Domini. This document granted permission to receive communion in the hand only in dioceses where this practice was already established (namely, in the Netherlands and surrounding areas). However, the same document reiterated that the preferred form of communion in the Catholic Church continued to be communion on the tongue.

[

The Supreme Pontiff has decided not to change the manner, long since received, of administering holy communion to the faithful. [...] But if the contrary usage, namely, that of placing holy communion in the hands, has already become established in any place, the same Apostolic See, in order to assist the Episcopal Conferences in fulfilling their pastoral office, which frequently becomes more difficult in current conditions, entrusts to these Conferences the task and duty of examining the particular circumstances, if they exist, but with the condition of preventing every danger of lack of reverence or false opinions concerning the most holy Eucharist from entering into the minds, as well as carefully suppressing other inconveniences.

It was therefore a painful concession in the name of peace, but considering it a impoverishing step backward and seeking to restrict its use to rebellious dioceses, making its extension difficult (requiring the approval of two-thirds of the bishops of an Episcopal Conference) and reaffirming that communion on the tongue remained the only permitted form, except for the mentioned exceptions, which are not approved but merely tolerated. The document explains that the worldwide episcopate, having been consulted, had largely expressed opposition to changing it. It also argues why communion in the hand would be a regression in Eucharistic practice. In fact, the entire document is a final appeal for rebellious bishops to set aside their claims and accept the universal norm of communion on the tongue.

Therefore, the Pope’s intention with this document was not so much to open the door to change, but rather the opposite: to erect a barrier to try to contain the rebellion and prevent its spread. The Pope acknowledged that communion in the hand had been possible in the early centuries, but considered it a progress in the right direction that had been surpassed, and reverting would be a regression that should be discarded. A reading of the complete document, which is brief, will confirm what has been stated here.

But as has been customary in recent decades, what begins as a concession, an exception, ends up becoming the norm. Despite the fact that almost no diocese met the conditions required to request the indult, while modernist heresy spread throughout the world, a Rome that was too lenient began granting most of the requests. By the 1990s, the exception was already permitted in almost every diocese worldwide.

John Paul II initially tried to stop new concessions of this indult, but ultimately he also yielded to the pressures. In 2004, he confirmed the situation in Redemptionis Sacramentum, number 92:

[

Although every faithful person always has the right to choose whether they wish to receive Holy Communion on the tongue, if the communicant wishes to receive the Sacrament in the hand, in places where the Conference of Bishops has permitted it, with confirmation from the Apostolic See, the sacred host must be administered to them. However, special care must be taken to ensure that the communicant consumes the host immediately in front of the minister, and no one walks away with the eucharistic species still in their hand. If there is a danger of profanation, Holy Communion should not be distributed to the faithful in the hand.

It is unnecessary to point out that consuming the host in front of the priest is often ignored, and there is almost always a risk of profanation. Also, the following is stated in Number 94:

[

It is not permitted for the faithful to take the consecrated host or the sacred chalice "by themselves, much less pass them from hand to hand among themselves."

This instruction is also disregarded, as it has become common practice to use laypeople to assist in distributing communion. It is also not uncommon to see in some First Communion masses how children are allowed to take the chalice themselves, something that is already normal at weddings for the bride and groom.

However, despite this increasingly widespread indult, the popes continued to teach that communion on the tongue is the only form ordained because it is the most respectful towards the Body of Christ, as Benedict XVI stated:

[

"The gesture of taking the Sacred Host and, instead of receiving it, putting it in our own mouth, diminishes the profound meaning of Communion."(La Repubblica, 31/07/2008)

And a year later, Mauro Gagliardi, consultant for the Office of Liturgical Celebrations of the Holy Father, stated the following:

[

Regarding receiving Communion in the hand, it is noted that this is possible in many places today (possible, not obligatory), but it remains a concession, a derogation from the ordinary norm which affirms that Communion is received only on the tongue. This concession has been granted to the Episcopal Conferences that have requested it, and it is not the Holy See who suggests or promotes it. (Zenit 25/12/2009)

Pope Benedict XVI then reiterated:

[

"When I decided that Communion should be received kneeling and administered on the tongue, I wanted to give a sign of deep respect and put an exclamation mark on the Real Presence... I wanted to give a strong signal: 'This is something special! Here it is, it is before Him that we fall to our knees.' (Light of the World: The Pope, the Church and the Signs of the Times. A Conversation with Peter Seewald, LEV, Vatican City 2010, p. 219)"

Successive secretaries of the Congregation for Divine Worship tried to promote a return to communion on the tongue, and Cardinal Ranjith even suggested abandoning the indult and prohibiting communion in the hand upon realizing that it had already become the common practice. He acknowledged that introducing it had been a mistake and sought ways to reinstate communion on the tongue and kneeling as the habitual practice of the whole Church. His successor, Cardinal Robert Sarah, left us these words in the prologue of Federico Bortoli’s book:

[

"It is a beautiful defense of the position of Popes Paul VI, John Paul II, and Benedict XVI. Let's focus on some phrases: 'Now we see how faith in the real presence can influence the way we receive Communion, and vice versa. Receiving Communion in the hand undoubtedly involves a great dispersion of fragments; on the contrary, attention to the smallest crumbs, care in purifying the sacred vessels without touching the Host with sweaty hands, becomes professions of faith in the real presence of Jesus, even in the smallest parts of the consecrated species: if Jesus is the substance of the Eucharistic Bread, and if the dimensions of the fragments are merely accidents of the bread, no matter how large or small a piece of the Host is! The substance is the same! It is He! On the other hand, lack of attention to the fragments leads to losing sight of the dogma: gradually the following thought could prevail: 'If not even the parish priest pays attention to the fragments, if he administers Communion in a way that allows fragments to be dispersed, then it means that Jesus is not in them, or that He is 'to some extent.' 'Why do we obstinately insist on receiving Communion standing and in the hand? Why this attitude of lack of submission to the signs of God? Let no priest dare to impose his authority on this matter by refusing or mistreating those who wish to receive Communion kneeling and on the tongue: let us come like children and humbly receive the Body of Christ kneeling and on the tongue." (Federico Bortoli, The Distribution of Communion on the Hand: Historical, Juridical, and Pastoral Profiles, 2018)

But one more step is still needed.

At present

The current situation for the Church refers to the post-lockdown times. By 2020, almost all dioceses had permission to allow communion in the hand, but in most parts of the world, many faithful still chose to receive communion on the tongue. All of this will change with the pandemic.

The arrival of Covid-19, with subsequent global lockdowns and the closure (for the first time in history!) of all churches, clearly marked a before and after. The Church’s suspension of sacraments citing health reasons sent, in the opinion of many, a clear message that saving bodies was paramount, while saving souls was secondary. When the churches reopened, a significant percentage continued to attend televised Masses or simply did not return; the Church itself had deemed it dispensable.

The pandemic and fear of contagion led communion to be considered a potential source of infection, prompting the Roman Catholic Church to prohibit communion on the tongue for two years. Everyone was required to receive communion in the hand, and those who refused were denied communion altogether or, at best, were invited to wait until the end of Mass to receive it, often in a dismissive manner and in a secluded area. There was also a widespread practice of discouraging or even refusing communion to those who wished to receive it kneeling. Since then, receiving communion kneeling and on the tongue has become rare. Ultimately, for various reasons, many priests and even bishops have come to view displays of deep devotion to the Eucharist as offensive. In essence, consciously or unconsciously, the same reform was implemented as the one undertaken by Protestants to eradicate belief in the real presence of Jesus.

Some may argue that receiving communion standing and in the hand does not inherently lead to a loss of belief in the real presence of Jesus in the Eucharist. They might point out that this is currently the form that has become the norm in the Catholic Church, and yet we still believe in the real presence. Oh, really? Think again, because the Pew Research survey of 2019 says otherwise: 70% of American Catholics no longer believe in the Real Presence (even less so in Europe).

Undoubtedly, there may be other factors at play, but if the same system worked with Protestants to eradicate that belief, what evidence do we have that this same system is not currently working to eradicate ours? The data indicates that it is indeed working.

We are flesh and blood people who inevitably perceive the physical as more real than the spiritual. That’s why Catholicism retains sacraments, rituals, images, and many other physical elements that allow us to physically experience spiritual realities and perceive them more intensely. Change the forms, and you will also change the meaning along with the associated beliefs. It’s not a spiritual law but a psychological one; humans operate in this way. That’s why the Church says “lex orandi, lex credendi” (the law of prayer is the law of belief)—as you pray, so you believe.

The document Redemptionis Sacramentum by Pope John Paul II makes it clear that the customary way of receiving communion in the Catholic Church is on the tongue, which is a right of all the faithful, although it allows for the exception of receiving in the hand in certain cases. This has not been changed: receiving communion on the tongue is a right, while receiving in the hand is an exception originally authorized only to maintain peace. However, currently in many parishes, these instructions are disregarded. Without any doctrinal or juridical basis but feeling justified by the “spirit” of established practices, it is difficult, and in many places even impossible, to be allowed to receive communion on the tongue. Kneeling before God seems offensive to many priests, and for some reason, they consider it their duty to extinguish these expressions of piety among the people, lest anyone continue to believe that the piece of bread they are distributing is actually the Body of Christ (note the irony).

Defenders of communion in the hand

There may be infiltrators whose objective is to destroy the Church from within (it is not paranoia, cases of numerous infiltrations have been revealed by the defunct USSR (see here), by the Freemasons (see here) and even by the gay lobby (see here). But that the enemies of the Church want to destroy faith in the Real Presence is understandable; what is more difficult to understand is why some priests and bishops who love the Church fight to impose a practice that in theory and In practice, it makes it more difficult for people to believe that this “piece of bread” is something more than a piece of bread. Of course, most of them defend this way in good faith and are convinced that it is the best; let’s try to understand their reasons:

Among those who defend communion on the tongue, the following arguments are common:

- They consider that this form highlights the “priesthood of the laity,” which was emphasized in Vatican II.

- They argue that, this way, the faithful participate more fully in the Eucharist.

- They believe that extending the hand to receive the bread is more respectful than putting the mouth forward to avoid touching it.

- It is faster and more comfortable for the priest.

- According to them, although they do not provide data, this was the way of receiving communion from Jesus until the 7th or 8th century.

- They claim, or at least used to claim, that the deep roots of this form in Tradition are such that it still exists today in part of the Eastern churches.

This last point was debunked by Pope Paul VI himself, who was compelled to write to all Eastern churches (in communion or not with the Pope) to inquire about this matter. All of them, without exception, denied such a practice.

And I cannot help but quote, as a curiosity more than anything, the Argentine Episcopal Conference when it states (see here) that “It is not easy to explain why they stopped taking communion by receiving the Eucharist in the hand.” I humbly recommend that you read this article of ours if you do not understand why the Church preferred communion in the mouth; and also to the archbishop of Monterrey, Mexico, when he affirms that receiving communion from the hands of the priest or from our hand does not matter, because at the end of the day “no hand is worthy of touching [the host], not even that of us priests.” of course” (see source). This makes some sense, but it conveys the idea that the hands of priests and laymen are comparable, when they are not. The priest in the consecration acts in persona Christi, so that it is the hands of Christ (using the priest’s body) that touch the host, and when giving communion we cannot forget that the priest’s hands are consecrated (in part by this reason that they are going to touch the body of Christ), while those of a layman are not. When there was the custom of greeting a priest by kissing his hand, everyone was very aware that those hands were special, sacred (and that is why they kissed them), but now almost no one is aware of it, not even the Archbishop of Monterrey apparently. Once again we see how seemingly banal external gestures greatly influence people’s beliefs.

Listening to those who not only defend receiving communion in the hand but prefer it or even abhor communion on the tongue, we see that their main argument, explicitly or implicitly, revolves around the idea that the image of a sovereign God before whom we kneel and whom we adore as infinitely superior to us is a “medieval” and obscurantist conception that we should abandon. They see Jesus as our brother; God became one of us, and therefore wants us to be on the same level as brothers and friends, not as subjects and creatures. For them, kneeling and opening the mouth is seen as an unworthy and humiliating act, as it goes against their idea of how our relationship with God should be. They view the Mass as less about adoration and sacrifice and more about a gathering of the assembly where Jesus is somehow one among many, albeit the principal one.

That idea of God as a homey is probably what prevails today, also known as therapeutic deism: God is a support, something that makes me feel good, whom I turn to when I’m sad or desperate. But it’s a God who doesn’t demand anything from me and therefore doesn’t have the power to change my life or transform me. When I don’t need Him, I leave Him alone and He leaves me alone.

But this God-homey or God-therapist is a thousand light years away from the God we find in the Bible. He is also not the God of Jesus, nor the God of the epistles, and He is certainly the complete opposite of the God (and Jesus) that we find in the book of Revelation. Nor is He the God of the first Christians, nor that of the Fathers of the Church, nor that of the Catholic Church prior to the 70s. He is a new God, generated by the modernists and that largely represents the triumph of certain Masonic ideas within the Church. The entire Bible, Old and New Testament, insists strongly that the so-called “fear of God,” along with love, is the foundation of the relationship between the Creator and his creatures. A fear fused with a great two-way love, of course, but fear. The fear that arises in the presence of the sacred, because if one truly realizes what is before him he cannot help but feel overwhelmed, as we see in the Bible over and over again. Saint Peter also reminds us that the fear of God is essential: “Love your brothers. Fear God.” (1 Peter 2:17).

It is evident that these people do not see the fear of God as something positive, and they consider that, on the contrary, we must break that fear and replace the Father God who demands conversion from us, with the Grandfather God who forgives us everything and demands nothing. That is why the new liturgy invented after the Council (and breaking with the Council’s instructions) eliminated from the Mass and the Catholic temples almost everything that helped create and maintain that notion of the sacred, turning everything into something mundane and everyday. In such an environment, worshiping the Eucharistic Jesus is certainly out of place, and the less it seems like we are dealing with a miracle, the better.

Another very frequent argument is the one presented in this video (minute 1:01:40) by the Argentine bishop Eduardo María Taussig who says: “The martyrs, the generation of the apostles, the confessors of the faith and even the Virgin Mary received the communion in the hand. Receive him on a throne, with outstretched hands, offering to the coming King to come as our Lord to sit on the throne of our person.”

As we have seen, the fact that the apostles and the first Christians received communion in the hand is something that we do not know but is probably false, but even if it were so, denying that the Church can evolve for the better, as it better understands the depth of the doctrines, would be to fall into the heresy of “archaeologism”, or what Pope Francis calls the sin of “indientrism” (or backwardism). And if it sounds good to receive Jesus “on the throne of our hands”, doesn’t it sound even better if we receive him directly on the throne of our entire body, letting Christ Himself (in the person of the priest) feed us, instead of daring to serve ourselves?

In that same video (at minute 1:18:26) we hear Monsignor Taussig scolding a priest who insists on giving communion on the tongue to the faithful who request it, and he says:

You have to tell him to put his hand and take communion. If there is any particle left, it is consumed, if not, there is no need to worry. The presence of Jesus is not in the invisible particles.

It is simply incredible that an entire bishop ignores the Church’s doctrine on the presence of Jesus in the Eucharist, which is not divided or diminished by fragmenting it, always remaining whole in each fragment, and the size of the fragment does not depend on our visual abilities, since it is not a subjective reality but an objective one, Jesus is there whether we see him or not (otherwise Jesus would not be present for the blind). But even if he were right, have you seen someone who, when taking communion in the hand, carefully checks his palm and fingers in search of tiny particles to consume with a lick? Have you heard any priest explain to people that he must do such a thing every time he takes communion? Rather, it all sounds like a farce to prevent people from taking communion on the tongue with strange excuses. That bishop, and many others who today think like him, should read the Catechism of the Catholic Church where it says:

[

The Eucharistic presence of Christ begins at the moment of consecration and lasts as long as the Eucharistic species remain. Christ is present whole and entire in each of the species and whole and entire in each of their parts, such that the breaking of the bread does not divide Christ. (CCC 1377)

And if someone, arbitrarily, admits the presence in the fragments but not in the “particles,” there are also citations where that word is used, such as in the very Council of Trent.

[

"If anyone shall say that, after the consecration, the body and blood of our Lord Jesus Christ are not present in the wondrous sacrament of the Eucharist, but only when received and not before or after, and that in the consecrated hosts or particles remaining or reserved after communion, the true body of the Lord does not remain, let him be anathema." (Trent, Eucharistic Canons, Canon 3)

Monsignor Taussig, we regret to inform you that Trent has just declared you an heretic and are excommunicated latae sententiae (that is, right away).

And this obsession with particles is not just a fixation of current traditional Catholics; it has been a concern since the early days of the Church, as we have seen before.

[

"Ye know, ye who are wont to be present at the divine mysteries, how, when ye receive the body of the Lord, ye do keep it with all carefulness and reverence, that not the least part thereof may fall, that nothing may be lost of the consecrated gift. Ye account yourselves guilty, and rightly so, if aught should fall through negligence." (Origen, Ex., h. 13, 3, circa year 245)

[

"Deem ye not now this as bread which I give unto you; take ye, eat this Bread of life, and scatter ye not the crumbs; for that which I have called My Body, that verily it is. A particle of its crumbs hath the power to sanctify thousands and thousands, and sufficeth to give life unto them that partake thereof." (Saint Ephrem, Homilies 4:4-6, circa year 360)

But if someone disagrees with all this and thinks that receiving communion in the hand is as dignified or better than receiving it on the tongue, and that the changes in the liturgy and catechesis have brought about great improvement, let’s leave theory aside and look at practice. Remember: In the United States, only 30% still believe that Jesus is truly present in the Eucharist; the remaining 70%, like Protestants, believe that the consecrated host is merely a symbol. Globally, surveys have shown similar results, and we must assume that the figures for Europe are even worse.

Before the changes that occurred after Vatican II (and we say “after,” not “because of”), the percentage of Catholics who believed in the Real Presence was close to 100%. But what is even more concerning, the majority of those who do not believe in transubstantiation (62%) affirm that “the Catholic Church teaches that the Eucharist is only a symbol,” so there is not even a rejection of that doctrine in them, but rather a lack of knowledge (they have not been taught this, nor have they seen anything in the Mass that makes them think of the Real Presence). Only 32% of those who do not believe know that the Church teaches it and still reject it; the rest reject it out of sheer ignorance (you can see the survey here).

We have done something very wrong in the last 60 years. Should we deepen the error or correct it? If, from childhood, we are taught to treat something with great reverence, we tend to consider it very special; however, if we are taught to treat it as something ordinary, it becomes exceedingly difficult to see it as anything other than ordinary.

The current instructions of the Church

In 2004, once the possibility (never obligatory) of receiving communion in the hand had spread to many dioceses in the world, the Vatican issued instructions, still in force, on how to correctly celebrate and administer the Eucharist. This is the document Redemptionis Sacramentum. Read the following quotes extracted from said document and assess for yourself whether your parish is complying or failing to comply with these instructions:

- Those who are conscious of being in mortal sin must not celebrate Mass or receive the Lord’s Body without first going to sacramental confession. (Number 81) (cf. 1 Corinthians 11:27-32)

- The priest celebrant is responsible for distributing Communion, if necessary assisted by other priests or deacons [not laypersons]. (Number 88)

- “The faithful receive Communion kneeling or standing, as established by the Conference of Bishops, with confirmation from the Apostolic See. When they receive Communion standing, it is recommended to make, before receiving the Sacrament, the appropriate reverence, which is to be determined by the same norms.” (Number 90).

- “Although each of the faithful always has the right to choose whether to receive Holy Communion on the tongue, if the communicant wishes to receive the Sacrament in the hand in places where the Conference of Bishops has permitted it, with confirmation from the Apostolic See, the sacred host should be administered to them. However, special care must be taken to ensure that the communicant consumes the host immediately in front of the minister, and that no one walks away with the Eucharistic species still in their hand. If there is a danger of profanation, Holy Communion should not be distributed to the faithful in the hand.” (Number 92)determined by the same norms.” (Number 90)

- “The paten for the Communion of the faithful should be held, to avoid the danger of the sacred host or any fragment falling.” (Number 93)

- “The extraordinary minister of holy Communion may administer Communion only in the absence of a priest or deacon, when the priest is prevented by illness, advanced age, or some other genuine reason, or when the number of the faithful approaching for Communion is so great that the Mass would be excessively prolonged.” (Number 158)

- “When an abuse is committed in the celebration of the sacred Liturgy, a true falsification of the Catholic liturgy is indeed performed.” (Number 169)

What if your priest denies you oral communion or you observe that any of the aforementioned norms are violated? Well, today there are even bishops who deny it, as you can see in this video:

- Any Catholic, whether a priest, deacon, or layperson, has the right to lodge a complaint about a liturgical abuse with the diocesan Bishop or the competent Ordinary who is equal in law, or with the Apostolic See, by virtue of the primacy of the Roman Pontiff. It is advisable, however, that the complaint or grievance be first brought to the diocesan Bishop whenever possible. This should always be done with truthfulness and charity. (Num 184)

Pope Francis has not changed this situation, as you can see in this video.

Conclusion

Communion on the tongue or in the hand? Both forms have historical roots. Both forms are allowed by the church today and therefore legitimate. But in view of everything written here we can conclude two things:

1- No priest can deny communion on the tongue, despite many cases where it is denied or individuals are compelled to endure discriminatory conditions (such as waiting until the end or receiving in another corner of the church). If someone is denied communion on the tongue, they can and should lodge a complaint with their bishop (cite the document Redemptionis Sacramentum). If the situation is not resolved by the bishop, it can be brought before the Pope (attach the email sent to the bishop and, if applicable, the bishop’s response).

2- It’s not about which form is legitimate; both are. It’s about which form is most appropriate. If we truly believe that the consecrated host is really the body, soul, blood, and divinity of Our Lord Jesus Christ, any respect, honor, and reverence we show is insufficient. To adore Jesus present before us by kneeling and ensuring that no particle, however small, might fall to the ground or become entangled in our clothing, is the most natural reaction of those who truly understand that the host or particles are Christ Himself.

The Apostle John was “the beloved disciple” of Jesus, his great friend, his adopted brother through Mary. Yet, when Saint John, in his visions of the Apocalypse, after many years of “separation,” sees his beloved Jesus before him again, his reaction was not to rush forward to embrace him or joyfully shake his hand. No, his great friend is the King of the Universe, the Almighty God, and upon seeing him, John tells us that:

[

And when I saw [Jesus], I fell at His feet as dead. But He laid His right hand on me, saying to me, “Do not be afraid; I am the First and the Last. I am He who lives, and was dead, and behold, I am alive forevermore. Amen. And I have the keys of Hades and of Death. (Revelation 1:17-18)

Note that Jesus doesn’t say to him, “Come on, John, enough with formalities and give me a hug, buddy,” but rather: “I am the Almighty…”

If John himself, Jesus’ brother and friend, upon seeing Him falls to the ground in His presence overwhelmed by such majesty (fear of God), not daring to even touch Him, Jesus Himself taking the initiative to touch him—is it too much to ask that those who approach to receive His Body kneel in adoration and allow themselves to be touched by Jesus, without daring to touch Him with their worldly hands? Is it worthy of disdain for someone who, convinced that the sacred form is truly Jesus Himself, would do anything to ensure that this same body, which can be fragmented but is always whole, does not end up trampled on the floor or spun in a washing machine? I recall the anecdote from a priest who mentioned that a parishioner would kneel in the sacristy every time he passed by the cleaning closet, and when asked why, he confessed: “Father, there are more bodies of Christ in the vacuum cleaner than in the tabernacle.” He had a point.

But setting aside any other considerations, the Church not only allows communion on the tongue but still considers it to this day as the correct and appropriate way to receive communion. Communion in the hand is seen as an indult, an exception (although now widespread), a concession to secularizing trends, or as its critics (rightly) say, “a reward for disobedience.” As we have seen, Rome initially granted this concession because it was unable to compel the bishops and priests of the Netherlands and surrounding areas to return to the then-only authorized form of receiving communion.

At the end of the day, the main criterion for discerning between one form or the other can be reduced to answering a fundamental question: how much respect and veneration do you consider you should show for the Body of Christ?

John Nelson Darby, a 19th-century Protestant theologian known for his role in the development of dispensationalism and founder of the Plymouth Brethren, once said:

"If I believed what you believe, that Christ is truly present in the Eucharist, I would not approach to receive Him on my knees, but prostrate on the ground with my face in the dust."

Note: All that has been explained here aims to help you make the best possible decision, but it should never be used to judge others. Both forms are permitted so that, as long as the Church does not say otherwise, the choice is a personal matter for each individual and no one else. More important than choosing one form or the other, though, is receiving Christ in the state of grace and with the necessary devotion and inner recollection. However, do not forget that external forms ultimately have a decisive influence on internal convictions, and together we create the environment in which future Catholics will be formed.

Leave a comment