All Protestant theology is based on a key doctrine: Sola Scriptura. This principle forms the foundation of their beliefs. This concept began with Luther and the Reformers of the 16th century. Let’s explore what it means and look at its equivalent in Catholic theology.

The Protestant doctrine of Sola Scriptura presents a fundamental paradox: while it is portrayed as a principle of absolute authority, its application relies on personal interpretations and lacks a unified criterion for defining essential doctrines. Protestant founders genuinely believed that by applying this principle, they would achieve a consistent theology faithful to the original Truth. They discovered their error within a few years. This individualistic approach, without an authority to establish doctrinal foundations, has since generated a wide range of contradictory beliefs among Protestants, revealing a structural weakness: the inability to establish a common truth within the Christian faith, as the early Church did, and, therefore, its ineffectiveness.

What is Sola Scriptura and what variations does it have?

“Sola scriptura” (in the ablative plural) means in Latin that we reach God’s Truth “by Scripture alone.” According to this doctrine, everything necessary for our salvation is contained in the Bible, sufficiently and exclusively, without the need for the Church, the sacraments, or any additional mediation; only faith in what it teaches is required. Moreover, proponents of sola scriptura hold that the essential biblical teachings on salvation are presented with such clarity (claritas scripturae) that anyone, without needing special training and with the help of the Holy Spirit, can understand them correctly. Therefore, the Bible is considered to have no ambiguities in the fundamental points of faith, allowing believers to access the truth directly without depending on an external interpretative authority. So for them, the Bible’s defining features are: exclusivity, sufficiency, and clarity.

Sola Scriptura:

- Exclusivity: The doctrine holds not only that the Bible is sufficient but that it is the sole source of authority on these essential matters.

- Sufficiency: The Bible contains everything necessary for salvation and does not require additional mediation from the Church or the sacraments.

- Clarity (claritas scripturae): The essential points of the doctrine of salvation are presented clearly, accessible to any reader with the help of the Holy Spirit, without the need for an external interpretative authority.

When Luther introduced the doctrine of sola scriptura in the 16th century, his main aim was not so much to reject Tradition as a source of religious authority, but rather to question it as a principle for interpreting Scripture. For the Catholic Church, biblical texts, like any other texts, can lead to multiple interpretations. This raises the question: how do we know which interpretation is correct?

For Luther, as we have seen, the Bible interprets itself; this is what he calls the principle of clarity. According to this principle, biblical texts are clear and free from ambiguity in essential matters. However, since human intellect can err even when faced with clear texts, there is a safeguard to prevent this risk: any Christian may invoke the help of the Holy Spirit to correctly interpret these texts, a concept known as the principle of private interpretation. If the texts are clear and the Holy Spirit guides the believer, what could go wrong?

Taken to the extreme, this doctrine asserts not only that religious truth is found exclusively in the Bible, but also that anything not explicitly present in it should be considered unbiblical and therefore condemnable. This extreme is quite common in popular Protestantism and is often the basis for rejecting and condemning certain Catholic doctrines, such as the Assumption of Mary, for example.

Today, a sector of Protestants favors a more moderate and practical version of sola scriptura. According to this view, the truth of faith is found only in Scripture, but certain traditions and even innovations can be good and useful, though not essential. They also tend to recognize the usefulness (though not necessity) of having pastors and theologians from their denomination serve as teachers to explain the Bible, in case someone does not fully understand it.

This moderate version is similar to that upheld by Methodists, who hold that other sources of Christian theology, such as Sacred Tradition, Reason, and Experience, are also important, though they are subordinated to Sacred Scripture as the primary authority. Appropriately, they prefer the term Prima Scriptura (primacy of Scripture) instead of sola scriptura.

This position is somewhat closer to the Catholic Church (Roman and Orthodox), which not only accepts Apostolic Tradition as a source of truth alongside Scripture but also considers that the only way to correctly interpret Scripture is by referring to Apostolic Tradition. Therefore, when a text can be interpreted in multiple ways, a good Catholic does not pray for inspiration to understand it correctly; instead, they accept the interpretation offered by the Church, which is based on how the early Christians understood it, that is, it is based on Tradition.

Where’s that in the Bible?

If Protestants build their theology on the premise that they can only believe what is written in the Bible and that the Bible interprets itself, the logical first step would be to validate that doctrine by finding where such a principle is stated within the Bible itself.

There are several quotes that are often presented as evidence that sola scriptura is a biblical doctrine:

[

Moreover, we possess the prophetic message that is altogether reliable. You will do well to be attentive to it, as to a lamp shining in a dark place, until day dawns and the morning star rises in your hearts. Know this first of all, that there is no prophecy of scripture that is a matter of personal interpretation, for no prophecy ever came through human will; but rather human beings moved by the holy Spirit spoke under the influence of God. (2 Peter 1:19-21)

[

But as for you, continue in what you have learned and firmly believed; knowing from whom you learned it, and that from infancy you have known the sacred Scriptures, which are able to give you wisdom for salvation through faith in Christ Jesus. All Scripture is inspired by God and is useful for teaching, for refutation, for correction, and for training in righteousness, so that one who belongs to God may be competent, equipped for every good work. (2 Timothy 3:14-17)

[

And for this reason we too give thanks to God unceasingly, that, in receiving the word of God from hearing us, you received not a human word but, as it truly is, the word of God, which is now at work in you who believe. (1 Thessalonians 2:13)

As we can see, these passages emphasize the importance, truthfulness, and usefulness of Sacred Scripture, but at no point do they state that this value lies exclusively in Scripture, excluding oral preaching. Moreover, these passages contain nuances that resonate more with a Catholic than a Protestant perspective. The first reminds us that Scripture cannot be interpreted individually; the second indicates that its purpose is “to equip for every good work,” that is, to lead to good deeds (contradicting sola fide); and the third refers to a faith that has already been proclaimed among the letter’s readers, not a faith they will learn by reading it. Nevertheless, when Protestants seek to justify sola scriptura in the Bible, they frequently present these three passages (and sometimes others even less relevant to the topic). So, what is happening here?

According to sola scriptura, truth is found fully and exclusively in the Bible; therefore, for this doctrine to be true, it would have to be clearly present in Scripture. Yet nowhere in the Bible do we find anything like this. As Scott Hahn recounts, when he was a Presbyterian professor of theology, a fellow theologian explained to him:

In reality, sola scriptura cannot be demonstrated from Scripture. The Bible does not explicitly state that it is the sole Christian authority. In other words, sola scriptura is, essentially, the historical confession of the Reformers in contrast and opposition to the Catholic claim that it is Scripture along with the Church and Tradition. For us, therefore, it is a theological presupposition, our starting point, not a proven conclusion.” (Rome Sweet Home, p. 53)

And shortly afterward, citing a conversation with another Protestant theologian, he recounts: “I asked another theologian, —For you, what is the pillar and foundation of truth?. He answered, —The Bible, of course! —Then why does the Bible say in 1 Timothy 3:15 that the Church is the pillar and foundation of truth? —You got me there, Scott. —I’m the one feeling caught. —But Scott, which Church would we be talking about? —How many contenders are there for that? I mean, is there any other Church that claims to be the pillar and foundation of truth? —Does that mean you’re becoming Roman Catholic? —I hope not. (Ibid., pp. 53-54)

Indeed, as that Presbyterian theologian affirmed, the Bible does not state anywhere that it is the sole foundation of truth. In fact, it explicitly asserts the opposite:

[

But if I should be delayed, you should know how to behave in the household of God, which is the Church of the living God, the pillar and foundation of truth. (1 Timothy 3:15)

Jesus did not command his disciples to write the Gospel but to go into the world and preach it. The later writings are considered a solid support for that preaching. But it was with the rise of Protestantism—coinciding with the invention of the printing press and the expansion of public access to books—that a new way of understanding Christianity emerged in Central Europe, based exclusively on biblical texts.

What is Apostolic Tradition?

The revelation Muhammad received came in the form of a book: Allah dictates the Qur’an to him, and Muslims received their faith through that text. In contrast, the revelation of the Christian God does not come in the form of a book but through a personal relationship. God does not dictate the Old Testament to Moses and that’s it; instead, He calls Abraham to form a Chosen People and gradually reveals Himself through that people, through patriarchs and prophets who educate them both with the spoken word and writings. With the coming of Jesus, revelation takes a leap, but again, God continues with His People, now called the Church. Within it, revelation—now complete—is transmitted first orally and later also in writing. Muslims are “people of the Book” and need nothing more; Christians are the “People of the Living Word,” the People of God.

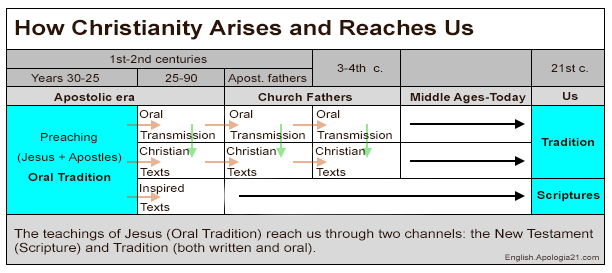

Jesus first, and the apostles and their disciples later, spread Christianity through oral preaching (Rom 10:17, Acts 8:25, Mark 16:15, Rom 10:14-15). During the first 20 years, it seems that none of the writings of the New Testament even existed, and yet it was during these first 20 years that the Church was established throughout much of the Empire. This is the beginning of what we call apostolic tradition, also called Sacred Tradition or simply Tradition, with a capital “T.” These are teachings that the apostles preached orally and were transmitted from generation to generation until today. This should not be confused with human traditions, written with a lowercase “t,” which may or may not be useful but are not a rule of faith or a foundation of truth.

Throughout the years, the early Christian Church began producing writings. By the end of the first century, a corpus of Christian texts emerged, including several letters from the apostles, one from Pope Clement I, biographies of Jesus, an early catechism and liturgical book, various apocalyptic accounts, and a pious book, among others. Over time, the Church recognized the infallible inspiration of God in some of these works (such as the Gospel of Matthew, the Revelation of John, and the Epistle of James), while others were deemed human works (like the Shepherd of Hermas and the Didache).

By the 2nd century, we already find numerous Christian authors writing about the faith or defending Christian doctrines against emerging heresies (such as the letters of St. Polycarp, Against Heresies by St. Irenaeus, and Tertullian’s Apologeticus). These authors are called Apostolic Fathers because they were direct disciples of the apostles (like Polycarp, a disciple of John, or Clement, a disciple of Peter and Paul) or disciples of those disciples (like St. Irenaeus, a disciple of Polycarp, who had been a disciple of John). These Apostolic Fathers knew Catholic doctrines firsthand or secondhand and were also familiar with the New Testament writings; thus, if any doubts arose, they could ask their teachers, just as these teachers could consult the apostles themselves. For this reason, their interpretation of Scripture has Authority: it is not a personal opinion, but a teaching from the apostles and their disciples that aligns with the common faith. In the rare cases where we find an opinion not accepted by the majority, such an opinion would automatically be disqualified, as it strayed from the golden rule of “what has been believed by all, always, and everywhere,” known in theology as the sensus fidelium (the [doctrinal] sense of the faithful). This golden rule was the criterion used by the early Church to discern whether a doctrine was authentic and came from the apostles or whether it was a heretical innovation that had to be rejected.

Finally, we have the Christian writings extending up to the time of St. Augustine (4th century), still close to the original sources and with access to many letters and other works of the earliest Christians, which have since been lost but helped them compile records, histories of Christianity, catechisms, liturgies, and more. These authors are known as the Fathers of the Church (which also includes the Apostolic Fathers). All of these writings from the 1st to the 4th centuries, and even into the 5th, are considered privileged sources for understanding Christianity as it was preached by Jesus and the apostles.

After the Middle Ages, the golden rule we just mentioned became practically unusable, as the Christian world became filled with heresies; however, by that time, it was no longer necessary either. Christianity had been established and consolidated around the 5th century, and although several dogmas would appear after that date, these were not new doctrines but beliefs that were already common in the early Church, now officialized. Thus, in practice, the golden rule became this: true doctrines are those believed by Christians in the early centuries, capable of being developed but not innovated. In other words, the earliest Tradition functions today for Catholics in a way similar to sola scriptura for Protestants; it is the golden rule for discerning truth.

Viewed this way, we can say that Scripture is part of Catholic Tradition: it emerged within it and is understood through it. However, for practical reasons, we now divide the sources of Christianity into two parts: Scripture and Tradition. Tradition begins with the teachings of Jesus and continues to this day (traditio means “what is handed down”). About 25 after Jesus, written texts begin to appear, so Tradition comes to have both an oral and a written part. Of this written portion, a small part (John 21:25) will be considered inspired by God and called Scripture; the rest, whether orally or in writing, will continue to be called Tradition. Over time, all these doctrines, ideas, and experiences that make up the oral Tradition gradually come to be reflected in written texts, especially up until the 5th century. Thus, we reach the present, where the apostolic teachings endure in the Catholic Church through these means:

Scripture and Tradition bring us the truth of apostolic preaching in two different ways.

- Scripture is inspired by God in its writing and, therefore, is infallible… as long as it is correctly interpreted. To ensure we interpret it correctly, we must look to Tradition to see how the early Christians understood it.

- Tradition, whether oral or written, is not infallible in itself; therefore, a rule was needed to identify possible errors: the sensus fidelium, supported by Jesus’ promises to His Church.

- CONCLUSION: Since Scripture is infallible, no doctrine from Tradition could be true if it contradicts Scripture, but it can be true even if it is not found in Scripture.

Practical Effects

Let’s now see the practical effects of all this.

Problem

Jesus says, “Take and eat, for this is my body… do this in memory of me.” How should this be understood—literally or allegorically?

Protestant solution

Applying sola scriptura, the Protestant takes his Bible and has to discern from it what Jesus truly meant. Ultimately, he concludes that, despite the principle of clarity, Jesus is not actually saying what it seems; rather, he was speaking allegorically. Thus, it’s acceptable to take bread and wine occasionally to remember Jesus, but the bread is only bread, and the wine is only wine—merely a symbolic gesture of remembrance. So symbolic, in fact, that many Protestants rarely observe it at all.

Catholic solution

For 2000 years, Catholics have been doing what Jesus commanded; for us, this is not a new issue to grapple with, but a fundamental part of Tradition. Therefore, no Catholic needs to investigate the meaning of this verse, as the Church has always known it (an uninterrupted transmission of Jesus’ teaching from the 1st century to today). Nevertheless, if there were any doubt, the Catholic solution is to ask what the early Christians believed about it. For example, we have the Didache from the first century, which describes the ritual of the consecration of the Eucharist and tells us that the bread and wine are “a spiritual food and drink of eternal life” (not merely a symbol). We also have St. Ignatius, appointed bishop of Antioch two or three years after the death of Peter and Paul, who, while criticizing the docetist heresies, accuses them of “not recognizing the Eucharist as the flesh of Jesus Christ.” In other words, a first-century bishop—who likely knew at least the apostles Barnabas and Paul, and especially John—clearly states that denying the Eucharist as truly the body of Christ is heresy.

It makes no sense for a 21st-century Christian, while meditating on a Bible verse, to reach a conclusion opposite to that of St. Ignatius, a disciple of the apostles, and still believe he is right and St. Ignatius is wrong. It is equally absurd to think that his pastor, or Luther himself, could understand the Bible better than those who, centuries earlier, learned these doctrines directly from Jesus or His apostles. The Christian writings of the 1st and 2nd centuries show that the original Church was clearly Catholic; this alone should be reason enough for Protestants to reject Tradition and choose to ignore it.

The Foundation of Tradition

The entire Protestant argument is clearly based on sola scriptura, as we have been seeing. We’ve also seen that this premise must simply be accepted by faith, since although Protestants believe all doctrines must be based on Scripture, this foundational doctrine itself lacks biblical support.

In contrast, Catholics base their beliefs on Tradition (including Scripture). Now, let us delve further into the Catholic foundation that Christian doctrines were recorded not only in the Bible but also in Tradition, which serves as the tool to interpret Scripture correctly. In the 1st and 2nd centuries, Christians clearly and emphatically defended the same present Catholic position:

[

Along with the interpretations [of the Gospels], I will not hesitate to add everything I carefully learned and remembered from the elders, because I am certain of its truthfulness. Unlike most, I did not delight in those who said much, but in those who teach the truth; not in those who recite the commandments of others, but in those who repeated the commandments given by the Lord. And whenever someone came who had been a follower of the elders, I would ask them about their words: what Andrew or Peter or Philip or Thomas or James or John or Matthew or any other disciple of the Lord had said, and what Aristion and the elder John, disciples of the Lord, were still saying, for I did not believe that information from books could help me as much as the word of a living, surviving voice. (Papias of Hierapolis, disciple of St. John, year 100, quoted by Eusebius of Caesarea in his Ecclesiastical History III, 39)

[

For by using the Scriptures to argue, they make them judge of themselves, accusing them either of not stating things rightly or of lacking authority, and of narrating things in various ways. The truth cannot be discovered in them if Tradition is not known […] And they end up disagreeing with both Tradition and Scripture. (St. Irenaeus of Lyon, disciple of St. Polycarp, who was a disciple of St. John. Against Heresies, III 2, 1-2. Year 130)

To make it clearer, we are setting aside the Old Testament and focusing on the New. Notice that in the New Testament, when it refers to “the Scriptures,” it is always talking about the writings of the Old Testament, among other reasons because the New had not yet been written or the canon had not yet formed:

[

For whatever was written in former times was written for our instruction, so that by steadfastness and the encouragement of the Scriptures we might have hope. (Romans 15:4)

Only in one case is there unquestionable reference to New Testament writings as part of the Scriptures, specifically to the epistles of Paul:

[

And consider the patience of our Lord as salvation, just as our beloved brother Paul also wrote to you, according to the wisdom given to him. He speaks of these things in all his letters, in which there are some things hard to understand, which the ignorant and unstable twist—to their own destruction—as they do the other Scriptures. (2 Peter 3:15-16)

But even here, to validate that certain letters of Paul are Scripture, one would first have to assume that this letter from Peter is Scripture—and the Bible does not state this anywhere.

This is important to consider, since, except for this citation, all references Protestants present about “the Scriptures” must be interpreted as referring to the Old Testament, not the New; in other words, they do not serve to prove their doctrine of sola scriptura. Moreover, if we only believe what the Bible says, then the only texts that would be inspired by God, and therefore part of Scripture (according to the current Bible itself), would be Paul’s epistles. And we do not even know if this refers to all the ones we have today or only those Paul had written by the time Peter wrote this letter (assuming, of course, that this letter of Peter is part of Scripture).

Therefore, we have the paradox that Protestants base all their doctrines on Scriptures whose authority depends solely on the judgment of a Catholic Church they consider pagan and full of errors. To say no, that the Church correctly identified the inspired books purely by chance, and that the foundation of the canon is the irresistible inspiration of the Holy Spirit… all right, but where is this idea that the Holy Spirit revealed the canon to a corrupted Church found? Is that concept in Scripture? Does the Holy Spirit list somewhere which writings are Scripture and which are not? No? The only New Testament book that claims divine inspiration is Revelation, precisely the one that took the longest to be accepted as an indisputable part of the canon. So, can the canon not be justified by sola scriptura? If so, then the entire structure collapses from its very foundation.

There is another instance where we are told again that Paul’s letters convey the Truth:

[

So then, brethren, stand firm and hold to the traditions that you were taught, either by word of mouth or by our letter. (2 Thessalonians 2:15)

Note that Paul does not testify to the sacredness (nor even the existence) of any authorized text except his own letters (and we still do not know exactly which ones these are). In this one passage, along with Peter’s, where the Bible testifies to the existence of true Christian writings, the Protestant has no choice but to accept that Paul is placing oral Tradition on equal footing with the written: “the traditions you were taught… by word of mouth” + “or by our letter.”

We all agree that the biblical texts record many of the teachings Jesus conveyed directly or through the apostles, but the rest of the apostolic preaching did not fall into oblivion; rather, it has remained alive in the Tradition of the Church (2 Thess 2:15, 1 Cor 11:2, 2 Tim 2:2) to this day.

Today, perhaps due to the novel fact of belonging to a civilization based on texts rather than oral traditions, even Catholics themselves tend to grant more reliability to what the Bible says than to what Tradition contains. However, this is more of a cultural distortion; as we have seen, it was not the case for the early Christians. To the two pillars of Catholic faith—Scripture and Tradition—we must add a third element: the Magisterium, which is the Church’s capacity to teach the Truth. We have already seen that the truth of Scripture is drawn out by applying Tradition, and the truth of Tradition is discerned by applying the sensus fidelium of the time. But beyond these human strategies, we have something far greater: a divine guarantee that the Magisterium cannot err in teaching false doctrines. This guarantee comes from the promises of Our Lord Jesus Christ, who, as both Tradition and Scripture affirm, will never abandon His Church or allow it to fall into error: (Mtt 16:18, 18:18, John 14:26, 16:13, Luke 22:31-32).

In practice, when Catholics and Protestants debate the truth or falsity of a doctrine, both typically turn primarily to Scripture, as it is the common ground that both sides recognize as true. However, for a Catholic, it is unacceptable to adopt the Protestant rules of engagement that say if something is not in Scripture, then it is false (sola scriptura), since this doctrine is a Protestant innovation. Likewise, it is unacceptable for a Protestant to accept that the apostolic Tradition of the Catholic Church comes from the apostles, as this would compel them to accept all Catholic doctrines.

However, it is possible to find common ground where both sides can argue on equal footing without abandoning the foundations of their faith. If a Protestant doctrine is not clearly found in Scripture, then the Catholic can argue that it is false (the discussion would center on whether the Protestant interpretation of a certain passage makes sense). Likewise, if a Catholic doctrine contradicts something that is clearly in Scripture, the Protestant can demonstrate that it is false (the discussion would again focus on the correct interpretation of that passage which supposedly contradicts it).

The failiure of Sola Scriptura

As we have seen, Catholics believe that the only way to interpret Scripture correctly, without fear of error, is by staying within the boundaries set by Tradition. Thus, if an interpretation leads to a contradiction with the beliefs of early Christians, that interpretation is clearly incorrect. (This also serves as a warning for many theologians today who call themselves Catholic but do not respect this fundamental principle, following their own judgment rather than seeking the light of the Church’s two-thousand-year wisdom). Furthermore, we have seen that Apostolic Tradition, our doctrines, and the authority of the Magisterium come directly from Jesus in an unbroken chain from Him to the present-day Church.

On the other hand, we have seen that Protestants believe they cannot fall into interpretive errors, even though they are separated from those texts by 15 centuries, for two reasons: the principle of clarity (the Bible is self-evident) and the principle of private interpretation (the Holy Spirit guides each reader). However, while such an optimistic stance may have seemed credible in the early years of the Protestant Reformation, time and the reality, which is stubborn, made it clear that things do not work that way. The best evidence that these Protestant principles of interpretation do not work is that those who thought this way have given rise to countless divisions that continue to multiply. And it wasn’t even necessary to wait centuries to see these effects; Luther himself, in his lifetime, witnessed the falsity of these convictions and, bitterly lamenting, had to admit:

There are as many sects and beliefs as there are heads. One person wants nothing to do with baptism; another denies the Sacrament; a third believes there is another world between this one and the Last Day. Some teach that Christ is not God; some say one thing, others another. If a rustic person, however unrefined, dreams or imagines something, he already believes he has heard the whisper of the Holy Spirit and thinks himself a prophet. (Grisar, Luther IV, 386ff)

And in a letter written to the Reformer Zwingli, he likewise confessed:

If the world lasts much longer, it will again become necessary, due to the various interpretations of Scripture now circulating, to accept the decrees of the councils and take refuge in them in order to preserve the unity of faith.

However, Protestants did not return to accept Catholic decrees and councils, making it impossible to maintain the unity of faith—even among themselves. It would have been beneficial for Protestants if Luther’s lament had sufficed to nullify the doctrine of sola scriptura, but everything continued as before. Today, the Catholic Church remains in harmony with the Church of the first century; our faith is essentially the same as that of Jesus’ disciples (albeit more developed and better understood). Meanwhile, Protestants have divided into multiple families with thousands and thousands of different denominations, which contradict each other and have increasingly distanced them from their origins to the point that some of them (Mormons, Unitarians, Jehova Witnesses, etc.) cannot even be considered Christians because they do not even believe that Jesus is God.

Conclusion

The reality of the diverse interpretations within Protestantism presents a critical problem for the doctrine of Sola Scriptura. If the Bible were so clear and personal interpretation of the Scriptures under the guidance of the Holy Spirit were truly infallible, there would not be such distinct and contradictory interpretations. In fact, even figures like Luther and Calvin differed on key points. This phenomenon suggests that, in practice, relying exclusively on individual interpretation leads to doctrinal fragmentation that is impossible to harmonize. Unless we assume that only a handful have correctly interpreted Scripture, it is contradictory to believe that the Holy Spirit infallibly inspires each reader. For Catholics, Tradition and the Magisterium offer a unifying guide that ensures the integrity of the faith as transmitted from the apostles.

It is essential to distinguish between the current diversity of opinions in some Catholic circles and the structural doctrinal fragmentation within Protestantism. In Catholicism, even if some individuals hold contrary opinions (such as not believing in the Real Presence in the Eucharist), this does not imply doctrinal variability but rather an individual’s lack of adherence to a single, unchangeable teaching, a heressy. In Protestantism, however, contradictory doctrines emerging under Sola Scriptura are not the result of individual interpretive errors but are inherent to the principle itself.

An even deeper issue is Protestant inconsistency in defining which doctrines are essential. For example, while some consider the Trinity or baptism essential, others believe that justification by faith alone suffices for salvation. This variability reflects a lack of objective criteria for determining essentials, leading to disagreements even on doctrines vital to salvation. Ironically, the only way to find two Protestants in full interpretive agreement is when they refuse personal interpretation and adhere to the magisterium proposed by their denomination, which, in effect, mimics the Catholic position of delegating doctrinal discernment to the Church.

In contrast to this ambiguity, Catholic Tradition and the Magisterium have maintained doctrinal continuity dating back to the apostles. Through councils and dogmatic definitions, the Church has resolved interpretative conflicts, preserving doctrinal unity and consistency throughout Christian history.

Something’s Wrong

If truth can only be one and lies can change and offer infinite faces, it is clear that Sola Scriptura is a tool of falsehood, and the doctrines based on it have no guarantee of being true. Only in specific cases where a Protestant agrees with a Catholic can it be claimed that this belief is the same as that of the Christians who forged their faith by listening to the apostles. So how have so many Ibero-Americans been seduced by this doctrine with the disastrous and simplistic argument that if it is not clearly stated in the Bible, it should not be believed? It seems that the Catholic Church has abandoned the formation of its faithful for decades and dedicated itself to other matters, leaving the flock unprotected against wolves. By looking down so much lately, it seems to have little to offer those who need to seek heaven.

In this other article, you can see a critique of sola scriptura based on arguments from the rules of logic:

(automatic English translation here)

Leave your comment (it will be published after review)